Prior to the late 19th century, housing options were limited to owning property or, as most people did, renting from a private landlord. The Housing of the Working Classes Act 1890 allowed local authorities in London to build council houses, and the first council housing was built in Bethnal Green in 1896. The Housing of the Working Classes Act 1900 extended this to the rest of the country, although it took a further 25 years for the first council houses to be built in Solihull Rural District.

In 1917, with the First World War still in progress, the Local Government Board asked councils to supply information relating to post-war housing accommodation. Solihull itself was a village at this time and was the administrative centre of a rural district with a combined population of 14,673, so did not have housing pressures on quite the same scale as more urban areas.

Health reports for Solihull

The Annual Report on the Health of the District 1914 noted six cases of overcrowding during the year – three in Olton and three in Solihull.

The report described the Solihull Rural District as having three chief centres of population – Solihull, Shirley and Olton – but remarked that Dorridge, Knowle, Balsall, and Packwood were rapidly developing as residential areas. It was noted that the only important industry within the District was that of agriculture, especially dairy-farming.

However, there was still an acute shortage of cottages in rural areas, and the 1914 Annual Report stated that in outlying areas such as Forshaw Heath, the only cottages available for certain large families were poor structures of insufficient air space.

It was noted in the Medical Officer for Health’s Annual Report in 1925 that workers from Birmingham who were unable to find accommodation in the city were moving into the Solihull district and erecting dwellings made from wood or corrugated iron, under the misapprehension that they could “live how and where they like in a rural district.” There were even reports of people living in disused furniture vans.

Solihull Rural District Council resolved at its meeting on 9th October 1917 to inform the Board that the Council would be prepared to undertake the preparation of a scheme for the provision of “a reasonable number of workmen’s dwellings on the conclusion of the War, on the assumption that financial facilities will be afforded by the Government.”

The Addison Act 1919

Following the end of the First World War in 1918, Parliament passed an ambitious Housing Act in 1919, often called the “Addison Act” after its author, Dr Christopher Addison, who was Minister of Health. This Act, reinforced by further legislation in the 1920s, gave local authorities a duty to develop new housing where it was needed by working people.

In June 1919, Solihull Council received a statement from its Special (Housing & Town Housing) Committee showing sites selected by them as suitable for “Labourers’ Dwellings” as follows:

- Site No. 1: Land situate at the junction of Earlswood and Birchy Cross Roads, Wood End, in the parish of Tanworth belonging to the Governors of the Tanworth Charity Estates (extent about 1 ¼ acres)

- Site No. 2: Land situate at Oldwich Lane, Fen End, in the parish of Balsall belonging to Mr Bromley (extent about ½ an acre)

- Site No. 3: Land situate at Marlhouse [?Malthouse] in the parish of Knowle belonging to Mr H. C. Smith (extent about 4 acres)

- Site No. 4: Land situate at Bentley Heath Road in the parish of Solihull belonging to Messrs. F. L. Thompson and A. E. Currall (extent about 4½ acres)

- Site No. 5: Land situate at Hockley Heath in the parish of Packwood belonging to J. Wykeham Martin Engineer (extent about 3½ acres)

- Site No. 6: Land (part of Arden Golf Links) situate in road leading from Solihull to Shirley and adjoining Great Western Railway line, belonging to Mr H. Nock (extent about 3 acres)

The Council resolved to apply to the Inland Revenue District Valuer for his valuation of the sites. Councillors also resolved to accept the offer of the Governors of the Tanworth United Charities to sell to the Council the land at Wood End for the purpose of building dwellings under the new Housing Scheme, at a sum of 9d per yard, plus the existing cottage, outbuildings, well of water and pump for an additional ninety pounds.

Although the six sites were purchased in 1920, and layout plans were approved for 250 houses, it does not appear that construction of any new council houses proceeded for a further five years. The site in Bentley Heath Road, Solihull was subsequently disposed of in 1922.

A survey of housing in 1919 by Dr Claude Edward Tangye (1877-1952), Solihull’s Medical Officer of Health, indicated that there were then 67 houses in the Solihull Rural District that should be closed down and a further 117 that were seriously defective.

Private enterprise

Some councils, including Solihull, were keen to encourage private enterprise rather than focusing on constructing dwellings directly. At a meeting of Solihull Rural District Council on 25th March 1919, a letter was read out from the Clerk to Stratford-upon-Avon Rural District Council asking for Solihull’s support for a resolution:

That this Council, whilst approving of the Government Housing Scheme, strongly urge that facilities be given to Landowners to build some of the required houses themselves and that the Government be asked to grant Loans to Landowners on favourable terms to defray the cost of erecting such houses.

Solihull Council resolved to adopt this resolution and to send a copy of the resolution to the local MP, the Local Government Board, and the Rural District Councils’ Association.

By 1921, it was reported by the Medical Officer of Health that:

The shortage of houses still continues, however, and it would appear very doubtful as to whether private enterprise will cope in any way with the situation.

Overcrowding

Local newspapers in the early 1920s carried reports of overcrowding, including at least 20 cases in Olton where young married people were living with parents (Birmingham News, 5th January 1924).

Twelve cases of overcrowding were reported to the Council in 1925 but the authority noted that only the most serious instances were reported, and most tenants were glad to have a house at all, irrespective of its condition or size.

The Medical Officer of Health’s Annual Report for 1925 mentioned the difficulty of improving housing conditions when an increasing population was not accompanied by the provision of working class houses. It was noted that the large and increasing amount of “better class houses” had naturally drained away the labour necessary for repairs, and has increased the difficulty of getting repairs done, even if the owner was willing.

The Medical Officer of Health’s Annual Report for 1930 observed that, since 1916, there had been growing in the District “colonies of shacks of all possible shapes and sizes, and of all degrees of comfort and structure.” These were erected on a number of sites, including the Mount Estate in Shirley, Major’s Green, Tythe Barn Lane, Whitlocks End, Dickens Heath, Solihull Lodge, Illshaw Heath, and at Robin Hood Allotments.

The dwellings on the Mount Estate, erected during and after the First World War, were described as huts that did not “conform even to a moderate standard of habitability.”

Resolution defeated

A headline in the Birmingham Daily Gazette of 2nd January 1924 – “Solihull District Council to build houses” – reported that Solihull Rural District Council was to formulate a housing scheme for submission to the Ministry of Health.

At a meeting of Solihull Council on 13th May 1924 a resolution was proposed that the Council should at once proceed with the erection of 24 working-class dwellings. A local councillor and Guardian of the Poor, Mrs Jane Nock (1872-1947), said that the distress caused by overcrowding in the district “was enough to make one shed tears.” (Birmingham Daily Gazette, 14th May 1924).

The Medical Officer for Health, Dr Lunn, reported that in one area, 63 people were living in 21 rooms. Supporters of the resolution to proceed immediately with the construction of these 24 houses argued that private enterprise had failed, and that the problem was getting worse instead of better.

Opponents argued that there was no mandate from ratepayers to embark on a building scheme and that the Council ought to wait for definite instructions from the Ministry of Health. The resolution to begin work immediately on the housing scheme was defeated by 10 votes to nine.

The “wrong type of houses”

In March 1924, Solihull Council attempted to encourage further building of houses by private enterprise by advancing loans to prospective owner-occupiers of up to 80 per cent of the market value of the house, not exceeding £650 per house. This approach was undertaken under the Small Dwellings Acquisition Act 1899, and the 30-year loans could be repaid weekly, monthly, quarterly or half-yearly.

When the topic of building council housing was discussed, it was emphasised that this would not cancel the existing loan-subsidy arrangements to owner occupiers. It was said that the subsidy had resulted in an enormous number of houses being provided and, as far as Solihull was concerned, the loan scheme had been extremely useful.

However, in March 1924, workers from Shirley complained that the houses being built in the Solihull rural area and receiving the subsidy were “not of a type suitable for the working classes.” The workers urged the Council to take up the matter earnestly and not leave the provision of houses to private enterprise.

The Women’s Village Council Movement

The Ministry of Reconstruction was established in 1917 to oversee the post-war rebuilding of national life. Chaired by Dr Christopher Addison, it established various committees, including the Women’s Housing sub-Committee. The aim was for women to be able to influence the design of the “homes fit for heroes” after the end of the First World War. The first Women’s Village Council (WVC) was established in Findon, Sussex in October 1917.

Solihull’s WVC had been established by the time of the Women’s Village Councils’ Federation first annual report in 1918, and it drew up a detailed housing enquiry form which was delivered to local cottages. Solihull Rural District Council was receptive to the results, setting up a special committee to look into the women’s suggestions, and making a report.

By April 1919, there were 15 Women’s Village Councils, with their main focus of interest being on housing. On its formation, each WVC sent a resolution to the Local Government Board asking that the Village Council be seen as representing the working women of their village.

Solihull Rural District Council reacted favourably to the proposed establishment of a WVC in Temple Balsall, noting the formation of this group at Solihull RDC’s meeting on 25th March 1919. It was recorded that the Temple Balsall Women’s Village Council sent a resolution dated 1st March 1919 to the Local Government Board as follows:

We have pleasure in reporting to the Local Government Board that the Temple Balsall Women’s Village Council (for the purpose of collecting evidence for the State-aided Housing Scheme) has been formed by general notice and now beg that we may be recognised as representing ‘working’ women in Temple Balsall and to ask that we may be consulted in all reforms and schemes connected with State-aided Cottages in our Village.

Minutes of Solihull Rural District Council meeting, 25th March 1919

In December 1919, the Ministry of Health issued a circular to local authorities, advising them to appoint Women’s Housing Advisory Committees. The Women’s Section of the Garden Cities and Town Planning Association invited women’s organisations to send in short accounts of the work they had accomplished, and an example given in the Common Cause, 3rd September 1920, noted that the Solihull Women’s Village Council had suggested the removal of a step between the scullery and the kitchen.

In Solihull, two “lady members” were amongst the five members elected to the Board of Guardians and the seven elected to Solihull Rural District Council in April 1922 – the first women to be so elected. The two ladies were Jane Nock, wife of an existing Guardian and councillor, Mr H. W. Nock, and Miss R. M. Bushell (who headed the poll, receiving the most votes of all the candidates). Both were nominated by Solihull Women’s Village Council.

Miss Rosetta Margaret Bushell (1876-1955) was the sister of Mr Warin Foster Bushell (1885-1974) who was Headmaster of Solihull School 1920-1927. Miss Bushell served on Solihull Council until 1927 when she resigned as a result of the family moving to Natal where her brother was taking up a Headmaster’s post.

The Housing Act 1923 introduced a fixed subsidy of £6 per house for 20 years – less generous than the Addison Act – to encourage house-building. Local authorities could allocate the subsidies but were not permitted to build houses themselves unless it could be demonstrated that the construction could not be done by private enterprise.

In 1923, an article in the Common Cause, the newspaper of the National Union of Women’s Suffrage, indicated that the Solihull Women’s Council had a scheme for building cottages, which would take advantage of the opportunities available to women under the Housing Act 1923. The article stated that women could take an active part in the effort to secure a supply of houses that would more adequately meet the shortage than at present exists.

The Solihull Women’s Village Council will be the first to take advantage of the Government Subsidy in their scheme for building four cottages in their village.

Common Cause, 28th September 1923

We haven’t been able to identify these four cottages with any certainty. In Solihull Council’s archives at The Core Library there are a number of plans dated 1923/24 for four dwellings but none mentions the Women’s Village Council. If you have any further information, please let us know (email: heritage@solihull.gov.uk)

Solihull’s first council houses

A change of Government in 1924 resulted in a change of approach to solving the problem of an insufficient supply of affordable homes for rent.

Instead of encouraging the building by private enterprise of houses for sale, the Housing Act 1924 – also called the Wheatley Act after the Minister of Health, John Wheatley – favoured the building of houses for rent rather than for sale. Interestingly, it was the first Housing Act to specify that houses should have a bath in a separate bathroom, rather than having a bath in the scullery.

On 30th September 1924, Solihull Rural District decided to apply to the Ministry of Health under the special conditions referred to in Sub-section (1) of Section 2 of the Housing (Financial Provisions) Act 1924 asking for provisional approval to erect “150 non-parlour type working-class dwellings” in the district.

The distribution of the homes would be:

- Solihull (including Olton and Shirley) – 60

- Tanworth-in-Arden – 32

- Knowle – 12

- Balsall – 12

- Lapworth – 12

- Packwood – 8

- Baddesley Clinton – 6

- Barston – 4

- Elmdon – 4

It was noted that once approval from the Ministry had been obtained, the Housing Committee would make arrangements as soon as possible to erect the first 26 houses. These would be the 12 at Knowle, eight at Packwood (Hockley Heath) and four of the allocation at Balsall.

Baddesley Clinton, Balsall, Barston, Elmdon, Lapworth and Tanworth were agricultural parishes, so the houses proposed to be erected in these places would be eligible for the increased Exchequer contribution of £12 10s per house per annum for forty years. The contribution required to be made by the Council was £4 10s per house per annum for a similar period.

Within nine months of the approval date (November 1924) the Council aimed to have the first 50 houses built – the 24 in Knowle, Hockley Heath and Balsall, plus 26 at Solihull.

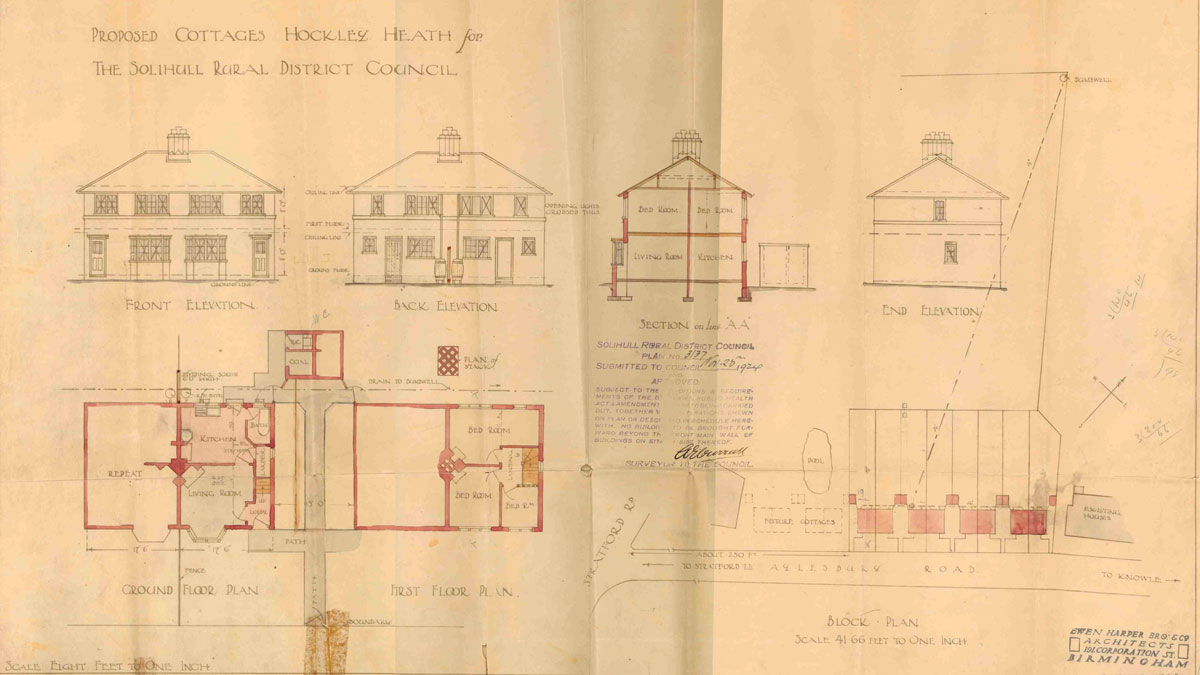

The first to be approved were eight houses in Hockley Heath, in the parish of Packwood, which were given planning permission in November 1924 (plan ref.: SOL/PS/1/2/3137, pictured at the top of this page) and were reportedly nearing completion on 2nd May 1925. There were said to have been 45 applications for the eight houses.

A Committee was appointed to select prospective tenants. They considered the claims of each applicant, and two or more members visited most of the houses to become personally acquainted with the conditions under which the applicants were living. Overcrowding existed in a considerable portion of the cases visited. Many had never occupied a house of their own, living in rooms, with parents, in very temporary wooden buildings or in vans (Annual Report of the Health of the District for the year 1930).

In 1925, approval was given for the building for a further 68 council-owned dwellings and, by the end of the year it was noted in the Medical Officer of Health’s Annual Report that 20 houses built by the local authority were occupied with a further 76 under construction.

By December 1925, 132 of the planned 150 houses had received planning approval, leaving just 18 (which were approved in 1926) to meet the initial target. It was then decided to erect a further 180 houses as part of a new scheme.

The houses that received planning approval in 1925 were:

- Four houses in Oldwich Lane, Balsall Common (Plan ref.: SOL/PS/1/2/3166)

- 12 cottages in Malthouse Lane, Knowle (SOL/PS/1/2/3160)

- Two houses in Friday Lane, Barston (SOL/PS/1/2/3206)

- 20 houses in Lode Lane and Wharf Lane, Solihull (SOL/PS/1/2/3200)

- Eight houses at Ilshaw Heath (SOL/PS/1/2/3256)

- 10 houses in Lyndon Road, Olton (SOL/PS/1/2/3304)

- 12 houses in Olton Road, Shirley (SOL/PS/1/2/3307)

In 1926, approval was given for a further 61 properties:

- 18 houses in Hermitage Road, Solihull (SOL/PS/1/2/3401)

- Eight houses in Bentley Heath Road, Solihull (SOL/PS/1/2/3463)

- 12 houses in Lode Lane, Solihull (SOL/PS/1/2/3534)

- Six houses in Stratford Road, Hockley Heath (SOL/PS/1/2/3583)

- Nine houses in Malthouse Lane, Knowle (SOL/PS/1/2/3597)

- Eight houses in Darley Green Road, Knowle (SOL/PS/1/2/3654)

In 1927, plans were approved for 86 new council homes:

- Four houses in Damson Lane, Elmdon Heath (SOL/PS/1/2/3707)

- 12 houses in Olton Road, Shirley (SOL/PS/1/2/3703)

- An additional four houses in Damson Lane, Elmdon Heath (SOL/PS/1/2/3781)

- Eight houses in Lode Lane, Solihull (SOL/PS/1/2/3789)

- 16 houses in Kixley Lane, Knowle (SOL/PS/1/2/3809)

- 20 houses in Alston Road, Solihull (SOL/PS/1/2/3835)

- Eight houses in Aylesbury Road, Hockley Heath (SOL/PS/1/2/3875)

- 14 houses in Kineton Lane, Hockley Heath (SOL/PS/1/2/3876)

In 1928, 50 new council houses were given planning approval:

- 12 houses in Lode Lane, Solihull (SOL/PS/1/2/3951)

- 20 houses in Alston Road and Damson Lane, Solihull (SOL/PS/1/2/3952)

- 18 houses in Olton Road and Streetsbrook Road, Shirley (SOL/PS/1/2/4061)

In 1929, the following plans for new council houses were approved:

- Four houses in Streetsbrook Road, Shirley (SOL/PS/1/2/4183)

- Six houses in Stratford Road and Aylesbury Road, Hockley Heath (SOL/PS/1/2/4194)

- 14 houses in Tythe Barn Lane, Shirley (SOL/PS/1/2/4228)

- 26 houses in Alston Road, Shirley (SOL/PS/1/2/4229)

Waiting list

Despite the building of more than 500 council houses in 13 years, demand was still exceeding supply as Solihull’s population was increasing at a rapid rate.

In January 1931, it was reported that there were 380 applicants on the housing waiting list, although a number were not resident in the Solihull Rural District and therefore did not qualify for the tenancy of houses provided by the Council.

In 1933, there were 16 cases of overcrowding reported, 14 of which were relieved by the provision of a council house.

Solihull’s Housing Committee recommended that proposals should be submitted to the Minister of Health for the provision of a further 100 houses.

The Medical Officer of Health’s reports indicate the total number of council houses occupied by the end of each year:

- 1925: 20

- 1926: 132

- 1928: 342

- 1930: 418

- 1931: 442

- 1933: 470

- 1937: 506

- 1938: 520

Locations

In 1932, Solihull’s local government status was changed from a Rural District to an Urban District, meaning that it lost some of the more rural parishes from its boundaries. This also included the associated council houses, which in the Medical Officer of Health Report 1931, were reported as:

- Baddesley Clinton – six houses

- Balsall – 12 houses in Balsall Street; eight houses in Barston Lane; six houses in Hob Lane; four houses in Fen End; 12 houses in Meer End

- Barston – eight houses

- Elmdon – eight houses

- Lapworth – six houses in Lapworth Hill and six in Station Road

- Tanworth-in-Arden – eight houses in Aspley Heath; four houses in Rushbrook; four houses in Springbrook; 26 houses in Terry’s Green, Earlswood

Meriden Rural District

A meeting of Meriden Rural District Council’s Housing Committee in June 1918 resolved that the Committee was not prepared to recommend to the Council that it consider a housing scheme.

The Committee stated that there was sufficient housing for the “ordinary population” but not for those relocating from large towns either side of the Rural District. Councillors remarked that it was not their duty to provide accommodation at the expense of local ratepayers for those who earned their living in these urban centres. The most that the Committee was prepared to recommend was the erection of 20 cottages, in pairs, to provide accommodation for the Council’s employees.

At a special meeting of Hampton-in-Arden Parish Council on 26th April 1920, villagers heard from Mr T. H. Negus, Sanitary Inspector and Surveyor to the Meriden District Council, who gave a review of the housing movement in the district. At the conclusion of the meeting a site was fixed upon, and various suggestions were given as to the building of the houses.

Fifteen months previously, Mr Negus said, he attended a conference at Birmingham, at which H.M. Inspector was present, and they were assured that as far as the working class in the district was concerned there was no shortage of houses. The acreage of the district was 55,000 and there were nearly 4,000 houses – 3,000 of which were below £16 rateable value. The district was an agricultural one, and as such there were more than sufficient houses to house the people, taking four or five per house.

After several consultations, however, the District Council decided to build 100 houses in eight groups, Hampton being one of the places selected, and the group would consist of 14 houses in a field in Bickenhill Lane, on the right-hand side past the plantation. The ground allotted to each house had been agreed by the District Council at a quarter of an acre, and Hampton Parish Council unanimously backed the allocation.

It was decided that the 14 houses would be built in pairs of three-bedroomed semi-detached dwellings. Two-thirds of the houses would be of the non-parlour type, with the remaining third having a parlour. It was recommended that all of the houses should have a w.c. and a bathroom upstairs, with sash windows. It was also decided that each house should have “a modern pig-sty.”

However, the proposed scheme was turned down by the Ministry of Health on the grounds of the price being too high. Alternative sites were investigated, including in Berkswell where difficulties were being encountered “owing to the principal landowners withholding any assistance.”

Pre-war council housing

The Medical Officer of Health’s report 1938 listed the distribution of council houses throughout Solihull Urban District:

- Solihull

- Alston Road – 60 three-bedroom houses; 36 two-bedroomed houses

- Cornyx Lane – 12 three-bedroom houses

- Damson Lane – 22 three-bedroom houses; eight two-bedroomed houses

- Heath Road – 10 three-bedroom houses; 12 two-bedroomed houses

- Hermitage Road – 26 three-bedroom houses

- Moat Lane – two four-bedroom houses

- Wharf Lane – 22 three-bedroom houses

- Olton

- Lyndon Road – 10 three-bedroom houses

- Lode Lane End – eight three-bedroom houses

- Shirley

- Olton Road and Streetsbrook Road – 46 three-bedroom houses

- Tythe Barn Lane – eight three-bedroom houses; six two-bedroom houses

- Cranmore Road – 52 three-bedroom houses; 21 two-bedroom houses; one four-bedroom house

- Clinton Road – one four-bedroom house; two three-bedroom houses; three two-bedroom houses

- Avon Road – six three-bedroom houses; two two-bedroom houses

- Monkspath

- Hay Lane – six two-bedroom houses; 18 three-bedroom houses

- Illshaw Heath

- Eight three-bedroom houses; 14 two-bedroom houses

- Hockley Heath

- Stratford Road – 10 three-bedroom houses

- Aylesbury Road – 16 three-bedroom houses; 12 two-bedroom houses

- Norton’s Green

- Eight three-bedroom houses

- Knowle

- Kixley Road – 16 two-bedroom houses

- Hampton Road – 30 three-bedroom houses

In addition to the above “subsidy council houses,” 26 “non-subsidy council houses” were listed in Lode Lane (five three-bedroom houses), Widney Road (12 three-bedroom houses), and Castle Lane, Olton (eight three-bedroom and one two-bedroom).

By 1940, it was reported that Solihull Council owned 546 houses (letter from Councillor J Woollaston to the Birmingham Mail, 4th January 1940).

In 1957, it was noted that there were 554 pre-war council houses in the Solihull Borough.

Differential rents scheme

On 28th March 1955, Solihull Council introduced a “differential rents scheme” for tenants of its council houses. This was a “model” rents plan claimed as the first of its type operated by a Midland authority. The means-tested scheme pre-dated statutory rent rebate schemes and the introduction of Housing Benefit.

Differential rents were intended to ensure that only tenants who could prove genuine need would get housing subsidy benefits. Others were expected to pay a “full economic rent” and the onus was on the tenant to claim the rent subsidy.

The three reasons for bringing in the scheme were given as

- those who can afford to pay the economic rent should do so;

- to help those who genuinely need even greater assistance than at present;

- to incorporate a “very necessary” increase to the repairs fund contributions.

The differential rents scheme was introduced initially for tenants of the Council’s 2,000 post-war houses, although rents of pre-war houses were increased by 2s weekly to cover the cost of the repair scheme to modernise their houses. Once modernised, the houses would lose their differential rents exemption.

The differential rents scheme meant an increase in rent of 10s per week for those paying a full market rent to the Council and not claiming a rebate. Those who claimed a rebate could usually save a few shillings per week on what they had paid before the introduction of the scheme.

The pre-war houses were initially exempt from the differential rents scheme on the basis that they lacked modern facilities. An article in 1964 noted that the houses were of good solid construction but many were built without hot water systems and they had outside W.C.s and no electric power circuits to modern standards. It was stated that most of them were of three-bedroom, family type with very few two-bedroom and four-bedroom houses.

Once the pre-war houses were modernised and the necessary amenities were provided, the properties would lose their differential rents exemption, meaning that most tenants would see a rent increase. In 1956, 18 pre-war council houses in Aylesbury Road, Hockley Heath, were brought up to modern standards and therefore came under the scheme.

In 1957, 24 pre-war houses in Olton Road and Streetsbrook Road were modernised and plans were announced for updating eight pre-war houses in Old Lode Lane, and 26 in Hermitage Road. The following year, expenditure of almost £6,000 was sanctioned for improving 32 houses in Alston Road and Cornyx Lane.

Solihull Community Housing

All of Solihull’s remaining council houses are now managed by Solihull Community Housing (SCH). This is an Arm’s Length Management Organisation (ALMO) set up by Solihull Council in April 2004 to run the housing service on behalf of the Council. Solihull Council still owns the properties but SCH delivers the housing services.

SCH is run by a Board of Directors made up of the Chair of the Board, three tenant members, three councillors and three independent people chosen for their specialist skills and experience.

SCH manages just under 10,000 tenanted homes and approximately 1,000 leasehold properties. They also look after just over 5,000 garages and a small number of shared ownership properties. They manage around 100 temporary accommodation units, supplemented by private sector leasing properties.

Almost three-quarters of the Council’s social housing is located in the wards of Chelmsley Wood, Fordbridge, Kingshurst and Smith’s Wood. The council houses in these areas were built as overspill housing by Birmingham City Council and were transferred by Birmingham to Solihull in 1980.

For further information see Solihull Community Housing’s website.

Further Reading

“The Role of the Women’s Housing Sub-committee” – Municipal Dreams website

Medical Officer of Health reports – Wellcome Collection

If you have any information about pre-war council housing in Solihull, please let us know.

Tracey

Library Specialist: Heritage & Local Studies

© Solihull Council, 2025.

You are welcome to link to this article, but if you wish to reproduce more than a short extract, please email: heritage@solihull.gov.uk

Leave a comment