The £44 million National Exhibition Centre (NEC) opened for business on 1st February 1976, the day before it was officially opened by H.M. Queen Elizabeth II. The NEC opened on a 310-acre site with six original exhibition halls – 1, 2, 3, 3a, 4 and 5.

Meriden and Solihull

When approval for the exhibition centre at Bickenhill was given in 1971, the site was owned by Birmingham City Council but was situated on Green Belt land within Meriden Rural District.

Under the original Government plans for the reorganisation of local government, Bickenhill would have been incorporated into the boundaries of Birmingham City Council. However, by the time that reorganisation plans were enacted in 1972 (coming into effect in 1974), Bickenhill was one of 10 parishes from Meriden Rural District that joined the new Solihull Metropolitan Borough so when the NEC opened, it was located within Solihull.

The need for a national exhibition centre

An annual general trade show, the British Industries Fair (B.I.F.), had been held from 1915 until 1957 (except 1925), with Castle Bromwich hosting shows 1921-1957. An industry referendum following the final B.I.F. in 1957 showed a preference for specialised exhibitions rather than general trade fairs and the Federation of British Industries set up a committee of inquiry under the chairmanship of George Pollitzer.

The Pollitzer Report 1959 concluded that trade exhibitions would play an increasingly important part in the UK’s export trade and that high quality promotional facilities were needed. It recommended that the Government and industry should sponsor a new exhibition centre in London.

A working group was set up in 1960 under the chairmanship of John Lord, with a report (A Plan for a National Exhibition Centre. Report of a Working Group Set Up by the Federation of British Industries) published in 1962. The report recommended the site of the Crystal Palace at Sydenham Hill but the project did not proceed past the report stage.

A subsequent report recommended that London be rejected as the proposed site, given the growing traffic problems in the capital. Northolt to the north-west was suggested as a more appropriate location but Birmingham also entered into discussions.

Existing facilities in London were considered inadequate and the Government was particularly galled that the Internation Textile Exhibition, due to be held in Britain in 1971, was not able to be accommodated as there was nowhere big enough to hold it. This single exhibition could have brought Britain £9 million in foreign exchange and the Government felt that the country was missing out on valuable opportunities.

Birmingham’s scheme approved

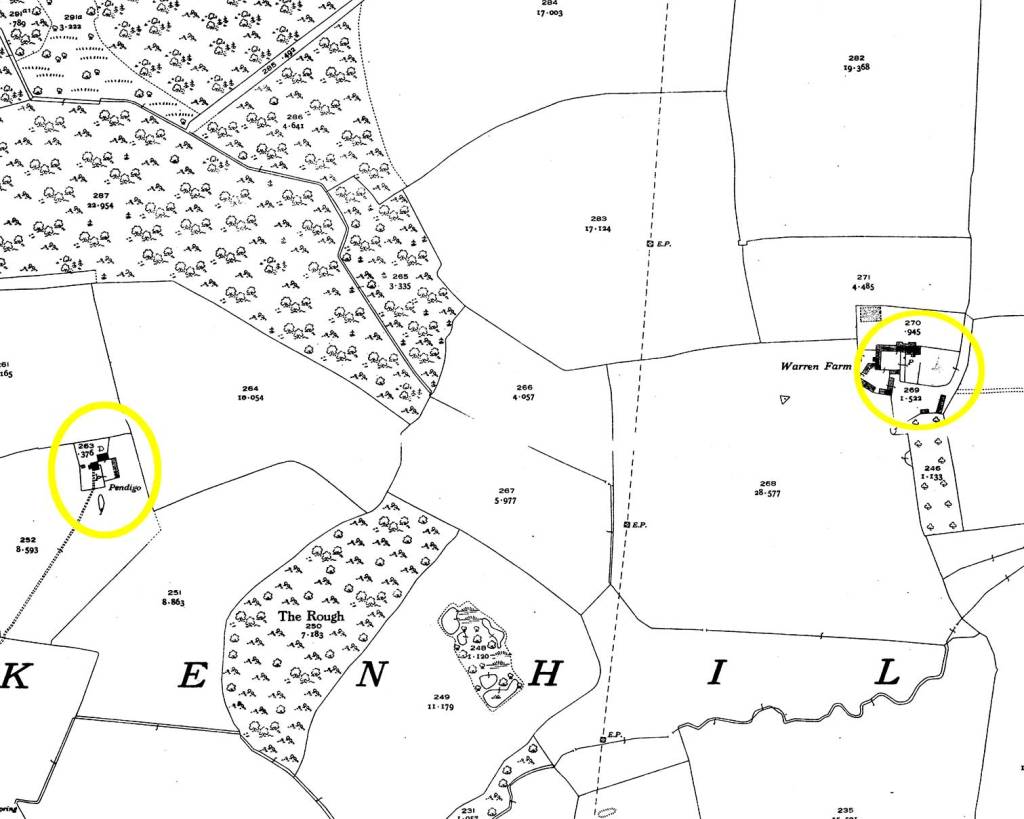

In 1969, Birmingham City Council purchased two adjoining properties – Warren Farm and Pendigo Farm – situated about eight miles from the city centre at Bickenhill, next to Elmdon Airport. The objective was to create in a parkland setting Europe’s finest exhibition and conference centre.

On 28th January 1970, Roy Mason, President of the Board of Trade, announced Government support for an exhibition centre to be built near Birmingham. Although three possible sites in Birmingham had been considered, the preferred site was Warren Farm, Bickenhill.

The reason given for Birmingham being selected was that the Government felt it could deliver a “viable development within a reasonable time scale.” Specific mention was made of:

- Birmingham City Council having a scheme prepared whereas London had not been able to produce a viable scheme

- Birmingham had magnificent communications by road, air and rail

- Land was cheaper in Birmingham – the land at Warren Farm had been acquired for less than £1,000 per acre, which would not have been possible in London

In May 1970 the National Exhibition Centre Ltd was formed jointly by Birmingham Corporation and Birmingham Chamber of Industry and Commerce, with four directors from each organisation and Frank Cole as the Chairman.

In June 1971, a public inquiry opened at Coleshill. In November 1971, outline planning permission was granted by Peter Walker, Secretary of State for the Environment. Detailed plans were submitted to Warwickshire County Council and the first bookings were announced!

A rival scheme for an exhibition centre at Northolt was announced by the Greater London Council and the Ronald Lyon developer group but planning permission was refused in July 1973.

On 16th February 1973, Prime Minister Edward Heath cut the ceremonial tape to set in motion a giant earthmover for work to start on the vast site at Bickenhill and unveiled a commemorative plaque marking the commencement of construction works.

The main constructor, appointed in January 1973, was R. M. Douglas Construction Ltd., Birmingham. N. G. Bailey and Co. was the main electrical contractor.

In September 1973, construction began on the Metropole Hotel and the conference complex, designed by Colonel Richard Seifert.

Construction of the NEC was completed on schedule in October 1975. The architects of the exhibition building, Edward D. Mills and Partners, devised a central core – the covered piazza through which all visitors first enter. Car, taxi and coach arrivals would enter through the main foyer, with rail and bus passengers arriving via the station bridge link.

A few weeks before the opening of the centre, members of the “Chelmsley Wood and Coleshill Fellowships of the Handicapped” were shown around the NEC as VIP guests. They were given a “marvellous” lunch and asked to point out any access issues they encountered at the venue.

Official opening

The Queen and the Duke of Edinburgh arrived at Birmingham Airport and were received by the Lord Lieutenant of the West Midlands, the Earl of Aylesford. The Royal party travelled to the NEC, where the Earl introduced the Lord Mayor of Birmingham.

The Queen unveiled a commemorative plaque in the Exhibitors’ Club before declaring the centre official open and pressing a button to activate the fountain in the Pendigo Lake, giving a signal to the soldiers of the Royal Regiment of Fusiliers to unfurl the flags of 30 nations at the entrance to the NEC. A brooch made by Waldron Gardener of Cheltenham was presented to the Queen at the opening ceremony.

The Queen and the Duke of Edinburgh made a 50-minute tour of the exhibition halls, making unscheduled stops at many of the exhibits that caught their eyes.

The Royal party then left for the Metropole Hotel where the Queen and the Duke of Edinburgh met overseas visitors, including ambassadors and high commissioners, in the Arden Room, before lunch was served in the Queen’s Hall.

After lunch, the Royal party returned by road to Birmingham Airport and were flown to RAF Marham near Sandringham.

Catering

Inside the halls were 10 self-service restaurants that could seat 200 people, as well as a “waitress-service” grill room seating 120 diners and bars serving buffet meals. On occasions, 20,000 lunches had to be served, with City of Birmingham Restaurants planning and carrying out the operation.

Above the piazza, the Griffin Restaurant – named after Sir Francis Griffin, leader of Birmingham City Council – served a full a la carte menu. There were also 12 private suites that exhibiting companies could hire for private entertaining. On the floor above the Griffin Restaurant, the 350-seat Exhibitors’ Club restaurant provided a cocktail bar and lounge for subscribing exhibitors and their guests. However, on the opening day of the first exhibition, there was a three-hour wait for a table at the Exhibitors’ Club as large numbers of the public had turned up for what was supposed to be a trade-only event.

First exhibitions

The six exhibition halls provided 1 million square feet of exhibition space – billed as being roughly the same as the combined capacity of Earls Court and Olympia. More that 3,000 double-decker buses could have been garaged inside the halls. The largest hall – Hall 5 – was capable of housing 35 ten-coach trains.

The first exhibition was the International Spring Fair, 1st-5th February 1976, which estimated that it would generate £600 million of export business for its 2,200 exhibitors. The first order was taken at 10:01 am, just one minute after opening, by Solihull firm W. A. P. Watson, which had moved to Vulcan Road in 1954.

About 10,000 buyers had been expected at the trade-only event but more than 75,000 people turned up on the exhibition’s first day, many of whom were sightseers and uninvited members of the public. This led to huge queues on roads leading to the centre and hour-long queues at restaurants and bars. Hundreds of motorists reportedly spent hours searching for their parked cars.

With expensive items on show on the stands, theft was foreseen, and £775 of watches had already been stolen by the time the fair opened, with luxury goods worth £500 reported missing during the second day. A Detective Superintendent from Solihull C.I.D. said that crime prevention officers would be discussing lessons learned with the centre’s own security staff.

Furnex 76 – the fourth International Furniture Production Exhibition – staged at the NEC 15th-19th March 1976, was the largest furniture production exhibition ever staged in England at that point, and the largest in Europe in 1976. It was described as being three times the size of previous events held in London.

Mach 76 – the Internation Exhibition of Machine Tools, Gauges and Tooling – held at the NEC 22nd September – 2nd October 1976, attracted so much interest that the organisers had to extend the original exhibition area beyond the planned 30,000 square feet.

The first sporting event was the World Table Tennis Championship 1977 with more than 1,000 competitors from over 100 countries expected.

The world’s largest independent exhibition organiser, Industrial and Trade Fairs Ltd, had moved its headquarters from London to Solihull in 1974 and was the NEC’s largest tenant, staging six trade events at the venue in 1976, plus a major public show – the Birmingham International Ideal Home Exhibition, held 14th-30th October 1976.

Transport

It was noted that the most important feature of the NEC at Bickenhill was the superb communication system. Elmdon Airport was in close proximity, with scheduled services to New York, Paris, Dusseldorf and Amsterdam and a compete domestic service.

A new terminal was planned as part of the expansion arising from the NEC, leading to the rebranding of the airport as Birmingham International Airport, which opened for business on 6th April 1984. As part of a strategic rebranding in November 2010 it became simply Birmingham Airport.

Travel to and from the NEC was described as “easy and cheap” in a Birmingham Daily Post special supplement, 2nd February 1976, with a bus ticket from Birmingham to the venue costing 17p and a ticket from Coventry costing 20p.

Road transport was expected to take much of the traffic to the NEC, with access roads being designed to join by means of grade-separated junctions with the M1, M6 and M40, as well as the A45, A452 and A464 trunk roads. The anticpated completion of the M42 would also give travellers the choice of two motorway routes to London and the south-east.

Work began on the railway station – Birmingham International – in January 1974. It was described as the first mainline station to be built in England since London Marylebone in 1899 and became operational on 26th January 1976.

The railway station’s covered concourse, above the five platforms, contained a travel centre, banking facilities, bookstalls and other public services. It was connected to the NEC by a wide, fully-enclosed bridge.

The opening of the new Birmingham International Airport on 2nd April 1984 was meant to coincide with a new feature for passengers travelling to the NEC. The Queen was present when the system was opened on 30th May 1984. However, it wasn’tuntil 16th August 1984 that Maglev – the world’s first commercial magnetic levitation system – opened for business.

It consisted of a two passenger cars each carrying 40 passengers and their luggage at a top speed of 40 mph. The cars were operated by magnetic levitation and linear induction motor above an elevated track. It took 90 seconds for the low-speed shuttle trip between the airport and the centre along a double-track 0.62-km guideway

Maglev was very popular with passengers and ran for 11 years before obsolescence problems and a lack of spare parts rendered it unreliable and it was closed in 1995. The majority of the elevated concrete guideway was reused by the cable-propelled Air-Rail Link people mover, which opened as SkyRail in 2003.

Pendigo Lake

Birmingham City Council’s architects designed a specially created lake, excavating some 300,000 cubic yards of earth to do so. The lake surrounds the Metropole Hotel and takes thousands of gallons of rainwater from exhibition hall roofs, roads and car parks. It is 17 acres in extent and 9ft deep.

The lake fountain, which was designed to aerate the lake, is capable of projecting water 100ft into the air.

The Birmingham Mail 8th June 1981 noted that the lake was home to about 10,000 carp, bream, tench and rudd.

In 1977, the first summer spectacular at the NEC saw Pendigo Lake encircled by crowds watching a kite-drawn water vehicle, water ski stunts, and a hovercraft race, during which entrants left the water and raced around the lake’s steep banks.

Water skiing demonstrations also took place on the lake on four days during the Motor Show, held in October 1978.

In 1986, a proposal to allow regular water skiing on the lake was refused by Birmingham City Council’s NEC and International Convention Centre Committee because of a “peaceful enjoyment” clause in the original lease agreed with the Metropole Hotel. The lease reportedly prevented the City Council from allowing the lake to be used for any purpose “other than for quiet sailing, boating or fishing, in any way that would detract from the enjoyment of guests” (Sandwell Evening Mail, 11th September 1986).

Expansion

A new hall – 6a – was built in 1978 to link with Hall 1 and cater for exhibitors’ staff meals. Capable of serving 1,000 meals at a time, construction of the new hall was completed within two months.

The Birmingham International Arena opened in December 1980 and was renamed the NEC Arena from 5 September 1983 , becoming the LG Arena on 31st August 2008 as part of a sponsorship deal following a £29 million refurbishment. On 6th January 2015 it was renamed the Genting Arena before becoming the Resorts World Arena on 3rd December 2018. In September 2024 it was renamed bp pulse LIVE.

In April 1989, the Queen returned to the NEC to open a new £40 million extension of three halls – 6, 7 and 8 – the completion of the first phase of a masterplan designed to double the size of the centre by the early 21st century.

The masterplan’s second phase saw the opening of four new halls – 9, 10, 11, and 12 – and a stylish atrium. These were officially opened on 9th July 1993 by Baroness Denton, providing an additional 33,000 square metres of exhibition space.

The glazed atrium linked the new halls to the existing seven halls via the Skywalk. There were also three new restaurants, seating a total of 1,500 people, as well as 3,000 additional car parking spaces, road improvements, a four-storey office development and workshop facilities.

In June 1996, the NEC Group announced plans for a £60 million scheme to expand the complex by 25 per cent, including four new halls. This was the third phase of a 20-year masterplan and outline planning consent was given by Solihull Council on 28th August 1996.

Birmingham City Council’s Finance and Management Committee gave the go-ahead in February 1997 and, for the first time, attracted private sector investment for the expansion. Media and exhibition group, EMAP Business Communications became a shareholder in a new company, National Exhibition Centre (Developments) Ltd, formed to raise the funds to finance construction of the new halls.

Concerns were expressed about the wellbeing of a herd of fallow deer living in the woodland and wetland conservation area around the NEC, with the new halls reducing the animals’ habitat by 19 acres. However, a fence was installed to prevent the deer from wandering onto the site, and strategically placed hoardings prevented the deer from being startled by lights from construction machinery.

Additional native trees (oak and ash) were planted to replace those lost to the development. The NEC Group also released 12 acres of land for ‘green’ development in association with Solihull Council, schools and local communities.

The £52 million Design and Construct contract was awarded to John Laing Construction Midlands Region in May 1997 and a topping out ceremony was held on 29th January 1998. The four new halls, numbered 17-20, were officially opened on Monday 7th September 1998 by Neil Kinnock, European Transport Commissioner. The new halls took the capacity of the NEC exhibition hall capacity to 190,000 square metres, making it three times larger than its next largest UK rival, Earl’s Court in London.

The construction of the four new halls reduced the car parking capacity by 3,000, leading to the NEC creating a ‘Green transport plan’ to encourage more visitors to use public transport. A new road linked the halls with the existing north perimiter Bickenhill Parkway road, allowing more flexibility in traffic management. A ‘central opportunity area’ was also created next to the halls to offer open air exhibition facilities.

In 2001, Hall 16 was opened.

In 2014, Birmingham City Council announced that it was to sell the NEC Group, which included the National Exhibition Centre, International Convention Centre (ICC), the LG Arena and the National Indoor Arena.

The following hotels were opened:

- 1999 – Express by Holiday Inn

- 2001 – Premier Inn

- 2002 – Crowne Plaza

- 2008 – Ramada Encore (later Ibis)

- 2020 – Moxy

Resorts World

In February 2008 it was announced that Solihull had been given permission to develop a large casino site, with the most likely location being at the NEC.

In June 2011, Solihull Council’s Licensing Committee granted a licence to Genting UK to build a £120 million casino and leisure complex on land at the NEC. Plans included a 10-screen cinema, 180-bed hotel and spa, conference and banqueting centre, designer outlet shops and 300 car parking spaces.

Resorts World Birmingham opened at 10am on 21st October 2015. The entertainment complex, loosely fashioned on a cruise liner model, was the fifth Resorts World destination and the first in the UK. A press release from Genting described it as “Europe’s first resort destination.”

The covered shopping village included 49 stores, 18 bars and restaurants, and the biggest casino in Britain. The Resorts World Cineworld was announced as having 1,782 seats in 11 screens, including the region’s first purpose-built IMAX screen in a multiplex cinema. The cinema opened on 23rd October 2015, in time for the release of the Bond movie, Spectre.

There was also an Asian-themed Santai Spa, and the first Genting Hotel in Europe. The four-star 180-roomed hotel opened to overnight guests on 2nd November 2015. The state-of-the-art conference and banqueting facility, The Vox, could hold up to 900 delegates and be separated into five halls at the touch of a button.

The Bear Grylls Adventure commenced construction in 2015. Run by Merlin Entertainments, the visitor attraction offered 11 experiences including a 65ft-tall high-rope course and shark dives

During the coronavirus pandemic, the attraction was forced to close. Operators Merlin Entertainments said in October 2024 that commercial challenges and the lasting financial effects of the pandemic meant that it had reluctantly taken the decision to close the attraction.

The Bear Grylls Adventure closed on 11th December 2024 and about 1,000 marine animals including sharks, rays, and tropical fish were re-homed to the nearby National Sea Life Centre Birmingham, as well as other to UK Sea Life sites.

Nightingale Hospital

During the Covid-19 pandemic, a Nightingale Hospital was developed at the NEC, with a hangar at Birmingham Airport ready to be used as a giant mortuary if needed.

The temporary hospital, built in eight days, was run by University Hospitals Birmingham NHS Trust and was officially opened by H.R.H. Prince William, Duke of Cambridge on 16th April 2020. It was a “step-down” facility, designed to accommodate up to 500 patients who were recovering from Covid, or who could not be treated by ventilation. If needed, there was the capacity to scale up the accommodation for up to 1,500 patients.

A week after opening, BBC News reported that the hospital had not yet been needed.

If you have any further information about the history of the NEC, please let us know.

Tracey

Library Specialist: Heritage & Local Studies

© Solihull Council, 2026

You are welcome to link to this article, but if you wish to reproduce more than a short extract, please email: heritage@solihull.gov.uk

Leave a comment