Isolation hospitals were set up to treat people who had infectious diseases such as smallpox, diphtheria, tuberculosis and scarlet fever in an attempt to prevent the diseases from spreading quickly through the population. Solihull is known to have had a “fever shed” and three purpose-built isolation hospitals 1870s-1980s.

The Workhouse Shed

Solihull’s first isolation hospital was a temporary wooden structure in the garden of Solihull Union Workhouse, Lode Lane. This “fever shed” was set up hastily in response to a smallpox outbreak in the area c.1870.

When it became known that Solihull had a means of isolating infectious patients, this resulted in numerous applications to the Board of Guardians “by persons not belonging to the pauper class.” The difficulty for the Guardians was that no one could be treated on workhouse premises without becoming ipso facto a pauper.

Following the Public Health Act 1872, Dr George Wilson, the newly-appointed Medical Officer for the mid-Warwickshire Sanitary District (which included Solihull and Meriden), made a recommendation on 21st May 1874 for a separate isolation hospital to be built.

A sub-committee was established to consider the matter and, at their meeting on 29th May 1874 they unanimously agreed to recommend to Solihull Rural Sanitary Authority that a site be found within two miles of Solihull on which to build a hospital.

Olton Isolation Hospital

The committee tried for some time to find such a site but, apparently, as soon as they opened negotiations with a land owner, someone else bought the site.

Almost despairing of finding somewhere suitable, they decided to monitor auctions and, on 18th July 1875, they bought a portion of land, sold under the Will of the late Samuel Thornley of Gilbertstone House (c.1807-1875), which was partly in Bickenhill and partly in Yardley. Controversially, this land was in the Lyndon Quarter of Bickenhill and was therefore in the Meriden Poor Law Union rather than the Solihull Union.

After the purchase was reported to the Local Government Board, two “memorials” were sent – one from the Board of Guardians of Meriden Union, and the other from landowners in Bickenhill. The “memorialists” objected to the proposed isolation hospital on the grounds that:

- the maintenance of the hospital would involve an importation of infectious cases into the Meriden Union

- it would necessitate the supervision of Meriden’s inspector of nuisances

- the site was in close proximity to a road much frequented, and in a populous part of Bickenhill

- the site was calculated to interfere with the prosperity of the parish

Following a public enquiry lasting two days, the site was approved and it was reported in March 1877 that the site was nearing completion.

The passing of the Divided Parishes and Poor-law Amendment Act 1876 satisfied the Solihull Guardians that the time had arrived for the Lyndon Quarter of Bickenhill to be annexed to the Solihull Poor Law Union, as had been recommended by Dr Wilson in 1874. It was argued that the Lyndon Quarter was completely isolated from Bickenhill and was almost entirely surrounded by the parishes of Solihull and Yardley. Both parishes were in the Solihull Poor Law Union but, following the Local Government Act 1894, Yardley Parish became part of Yardley Rural District, whilst the parish of Solihull became part of Solihull Rural District. The two councils established a Joint Isolation Hospital Committee to oversee the management of the hospital.

Yardley Rural District included the suburbs of Sparkhill, Acock’s Green Hall Green, Tyseley, Greet, Hay Mills, Stechford and Yardley itself.

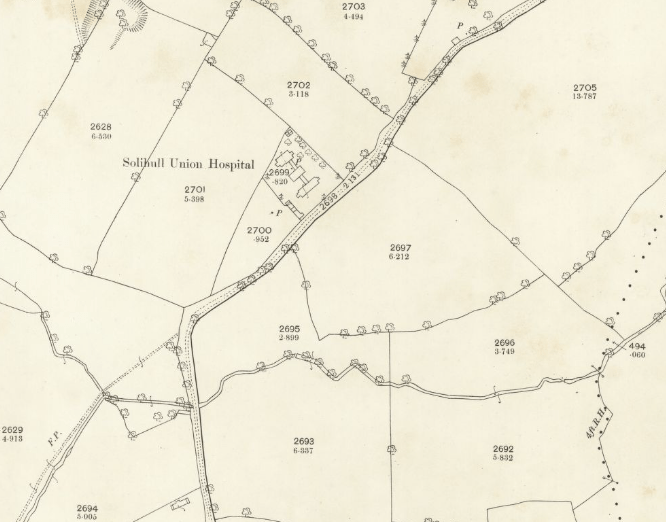

The Solihull Union Hospital, or Solihull and Yardley Joint Isolation Hospital – sometimes also referred to as Olton Isolation Hospital or Bickenhill Isolation Hospital – opened in Wagon Lane at the beginning of October 1877 (Leamington Spa Courier, 27th April 1878). By the end of the year it had seen seven admissions – five for scarlet fever, one for diphtheria and one for typhoid fever. All of the patients recovered.

Reproduced courtesy of the National Library of Scotland

According to Joy Woodall in Information from Gin, Ale, and Poultices… Lasers and Scanners: Solihull Workhouse and Hospital 1742-1993, Olton Isolation Hospital cost £2,045 and held 12 patients. There was a resident Master and Matron and a special ambulance. Initially Dr Edward Sutton Page was Medical Officer but was soon succeeded by Dr E. H. Hardwicke. The charge per person was £2. 2. 0 plus £3. 3. 0 to the Medical Officer. In its first three years it dealt with 50 cases.

Smallpox Hospital

The first meeting of the Solihull and Meriden Rural District Councils Joint Smallpox Hospital Committee took place on 25th November 1902. It was resolved that Solihull Rural District Council be recommended to purchase from Mr Joseph Currall for £120 a site at Marston Green for the erection of a smallpox hospital.

On 3rd February 1903, the committee instructed the clerk to apply to Warwickshire County Council to issue an Order constituting Solihull and Meriden Rural Districts a Smallpox Hospital District under the Isolation Hospitals Act 1893. The district would be called the Solihull Smallpox Hospital District.

Plans for a permanent hospital were submitted to Solihull RDC on 17th March 1903 but the council referred the proposal back to the joint committee to consider how costs could be reduced and how the money could be raised. In the meantime, the King’s Norton Smallpox Hospital Committee had indicated that it would accept patients from Solihull and Meriden at a cost of £4 4s per week per case if there were already patients from the district in the hospital, or £5 5s per case when there no existing cases from the district being treated.

By April 1903, the surveyor, Mr A. E. Currall, had submitted plans for a temporary corrugated iron building (cost £1302) as well as his original proposal for a brick building (cost £2250). Solihull would pay the greater proportion of the cost – the ratio of 14:11 reflecting the respective populations of Solihull and Meriden.

The proposal for a corrugated iron building was accepted, and the tender of Messrs. Bragg Bros, for the erection of foundations (£522) and of Mr W. Harbrow, of South Bermondsey, London for the erection of the corrugated iron building (£662, including £152 for an administration block) was accepted. The hospital would be 400 yards from Marston Hall, the nearest building to the site.

Objections to the chosen site were received by the Headmaster of King Edward VI School, Birmingham (R. Cary Gilson, who lived in Marston Green), and the Guardians of the Parish of Birmingham. Mr Cary Gilson had a house on the same road, a mile away from the proposed hospital, but said that he was objecting on the grounds of the unsuitability of the site, not because of his proximity to it. He said he had not heard of anyone in the district, apart from some members of Solihull District Council “who did not think the project insane.”

Mr Wingfield Digby offered a site on his Coleshill Estate in exchange for the land at Marston Green, but the Medical Officer for Health, Dr G. Wilson, expressed his satisfaction with the existing site and the Council resolved to proceed with the erection of the hospital.

The site was apparently on the main road between Elmdon and the Coventry Road to Marston Green Station, with a stream on one side that invariably flooded in rain. A letter to the Birmingham Post, 20th April 1903, stated that the site was the lowest in the district and was continually under water. The author questioned sarcastically whether fog and mist and damp were a new cure for smallpox, wondering whether the committee would keep a boat for use in winter months!

At the meeting on 24th November 1903, John and Ellen Harrison were appointed as caretakers from 1st March 1904, living in the adjoining cottage rent-, rates- and taxes-free, and being supplied with fuel. In return, Mr Harrison was to look after the Institution, attend to the garden and make himself generally useful under the supervision of the Steward. Mrs Harrison was to keep the premises clean and when the hospital was occupied, to nurse and cook for the patients and do the necessary washing.

The hospital was completed and ready for the reception of patients by 15th March 1904. Mr William Harris was appointed Steward will effect from 26th March 1904, with an annual salary of £5.

The Medical Officer of Health’s Annual Report for 1913 stated that the Smallpox Hospital, which it described as being in Sheldon, could provide for 16 cases and was kept in a state of readiness by the resident caretaker and his wife, under the direction of the Steward.

The Smallpox Hospital at Marston Green was closed in 1933 and cases were instead sent to Witton Hospital in Birmingham.

Meriden Rural District

On 29th May 1903, the Coventry Herald reported that negotiations had taken place in 1901 with a view to Meriden Rural District Council becoming a partner in the Solihull and Yardley Isolation Hospital. Apparently, two sub-committees were appointed but never actually met. The committees were felt to be too large, and the distance was inconvenient. This meant that, despite several attempts, it hadn’t been possible to agree a meeting date and location.

By 1903, the options were either to extend the hospital, or for Yardley to withdraw from the partnership. Yardley had been trying to find an alternative site, either on its own or jointly with Solihull. However, it was remarked that even if such a site could be secured, it would take an additional two or three years for Meriden to be able to join the combination.

Small infectious hospitals were expensive to build, equip and maintain. They could also have long periods when they were empty, meaning that they could not always be made ready quickly when required. It was pointed out in 1903 that the district had outgrown the accommodation and that Solihull was in the position of having to contribute to the hospital but not being able to send patients there as there was insufficient capacity. It was felt that it would be better for Solihull to unite with a smaller district like Meriden, leaving the larger district of Yardley to provide a hospital of its own.

The Coleshill Chronicle, 26th September 1908, reported that Solihull had now joined with Meriden Rural District Council and was seeking approval from the Local Government Board to borrow £6,500 for the purchase of land near Berry Hall for the erection of a new isolation hospital. The cost of the new hospital was £11,650 but it was estimated that the annual maintenance would cost Solihull no more than £250 per year, compared with £446 for the Olton Joint Hospital. It was also pointed out that “the injustice of the present system” was shown in September 1908 when the Olton hospital was full, but only one patient from Solihull was receiving treatment there.

An article in the Birmingham Mail, 16th February 1910, referred to an agreement made in July 1909 for Yardley Rural District Council to purchase from Solihull Rural District Council its share in the Isolation Hospital, Lyndon End, Olton. Under the agreement, the Yardley Council was to pay £1,000 for the premises, £200 for furniture and other property, and £50 for legal costs. Yardley would also take on the outstanding portion of the loan, £951 13s 8d.

Yardley intended to extend the isolation hospital so that it could accommodate people with diptheria or typhoid, in addition to the scarlet fever patients it had previously treated. A public inquiry was held in 1908 into the Council’s application to borrow £1,000 for the purpose of buying land adjacent to the hospital to create an extension.

Greater Birmingham

In January 1910, a Local Government Board enquiry was held into the proposal to extend the boundaries of the City of Birmingham to include the outlying districts of Handsworth, Aston, Erdington, Yardley, King’s Norton and Northfield. Following initial opposition, Yardley came to an agreement with Birmingham in November 1910.

On 9th November 1911, Yardley Rural District became part of the City of Birmingham under the Local Government Board’s Provisional Order (1910) Confirmation (No. 13) Act 1911, (sometimes called the Greater Birmingham Act) which received Royal Assent on 2nd June 1911. The Poor Law administration was unified under the same Act with effect from 1st April 1912, meaning that this was the date that Yardley separated from the Solihull Poor Law Union.

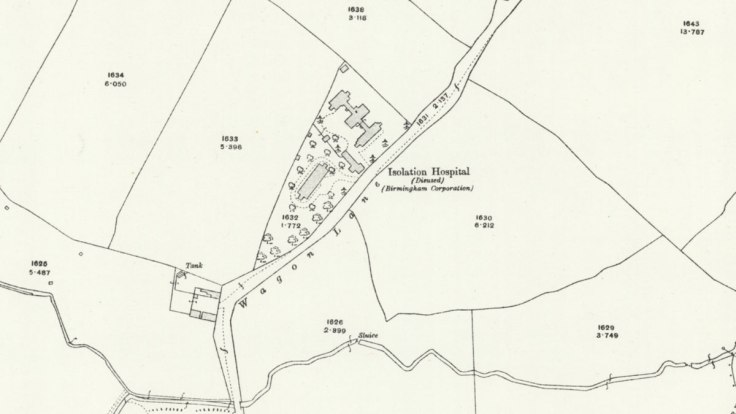

Birmingham had its own isolation hospital at Witton, so it seems likely that the isolation hospital on the Wagon Lane site soon became surplus to the city’s requirements. By 1913, the hospital was marked on maps as disused. The buildings were still there by 1938, but had become part of Lyndon Playing Fields and were apparently used as a sports pavilion. The playing fields were used to grow crops during the Second World War, reverting to grass following the final harvest of 17 acres of wheat in 1945.

After the war, the former isolation hospital buildings became a youth centre and baby clinic, run by Solihull Council. However, the Birmingham Mail, 28th November 1968, reported that Birmingham City Council, which owned the park, had given Solihull Council notice to quit the site earlier in the year. The city council wanted to turn the buildings on the edge of the park in Wagon Lane into changing rooms and showers for football teams using pitches there.

The land, although owned by Birmingham, was within the Solihull Borough boundary so it was to Solihull that Birmingham Parks Department had to apply for planning permission to convert the former isolation hospital building on the site to provide 20 dressing rooms for people using the playing pitches.

Reproduced courtesy of the National Library of Scotland

Catherine-de-Barnes Isolation Hospital

The Joint Isolation Hospital at Catherine-de-Barnes (pictured at the top of this page) was built by Solihull and Meriden Rural District Councils and was opened on 1st October 1910 by Mr W. Letts, the chairman of the Joint Isolation Committee (Birmingham Mail, 3rd October 1910). It was to be Solihull’s third and final isolation hospital.

The hospital was built by Mr H. Gregory, of Olton, from the designs of Messrs. W. H. Ward and Son, Birmingham. The building was designed for fifty-six patients, and had separate blocks for the treatment of scarlet fever, diphtheria and typhoid cases. There were also official and administrative blocks. Owing to the hospital being outside the water and gas supplies, a well and electric light dynamo were installed, with the power coming from a 16-h.p. steam engine, which also drove the laundry machinery etc.

The opening of the new hospital, which was situated on the corner of Henwood Lane and Berry Hall Lane, meant that patients from Meriden Rural District no longer had to travel to Coventry for treatment.

At a meeting of the the Meriden Guardians and Rural District Council on 22nd November 1910, it was reported that the new hospital was ready to receive patients and that, as a result, the agreement with Coventry should be terminated. The resolution was passed, with thanks given to Coventry Corporation “who had helped them out of a great difficulty,” (Coventry Evening Telegraph, 22nd November 1910). The agreement was subject to three months’ notice, so formally ended on 24th February 1911.

In December 1910, it was agreed to accept at the new isolation hospital cases from outside Solihull and Meriden, if there was space available. It was hoped that the admission of outside cases would offset some of the expense of the new building, as well as giving the staff something to do when they were not busy. Reportedly, one nurse had already left as there was nothing to do. The charge for outside patients was fixed at 1½ guineas per week, plus 5s for the doctor.

The Medical Officer of Health for Solihull noted in his annual report of 1913 that the isolation hospital at Catherine-de-Barnes had provision of 14 beds for scarlet fever, six for diptheria and four for enteric fever. During 1913, the hospital dealt with 45 cases of scarlet fever, two of diptheria and one of typhoid. Sixteen of the scarlet fever cases were as a result of an epidemic at Tanworth, which necessitated the closure of the village school 24th September to 20th October 1913.

Post-natal and maternity hospital 1950-1966

When these infectious diseases became less prevalent, the hospital at Catherine-de-Barnes became used as a post-natal hospital, with the first five patients arriving on Tuesday 9th October 1950. The Solihull News, 13th October 1950, reported that the hospital introduced a new idea into midwifery in the district. Within a few days of giving birth in Netherwood or Brook House maternity homes in Solihull, mothers would be transferred to the post-natal hospital at Catherine-de-Barnes “where they may enjoy ideal conditions and treatment.” The new arrangement would also help to ease the acute shortage of maternity accommodation in the district.

Catherine-de-Barnes maternity hospital closed suddenly in May 1966, when a smallpox outbreak began in the Midlands. It re-opened almost overnight as a smallpox hospital, with maternity patients moving out and the first patients moving in within a few hours of the workmen beginning work.

Smallpox outbreak 1966

Six patients were admitted to Witton Hospital with smallpox and were moved to Catherine-de-Barnes on 5th May 1966. On 7th May two more patients were admitted to Catherine-de-Barnes from Stoke-on-Trent, with two patients from Willenhall being admitted on 9th May. By 10th May it was reported that there were 24 known cases since the disease was first discovered in the Midlands 11 days previously.

Five more cases from Stoke were admitted to Catherine-de-Barnes Isolation Hospital on 13th May 1966, with a further patient from the area admitted on 15th May. Two more people from Stoke and one from Walsall were admitted on 17th May, bringing to 19 the total number being treated there, and the number of Midlands cases as 33.

A Government report into the later 1978 smallpox outbreak mentions that 78 people were affected by the outbreak in 1966 and that the primary case was thought to be a medical photographer employed in the Anatomy Department of the University of Birmingham Medical School.

The Catherine-de-Barnes isolation hospital closed the doors on its last patient on Saturday 25th July 1966, with staff moving out the following Wednesday. This ended its eight-week spell as a smallpox hospital. During this time, the hospital dealt with 31 patients, none of whom was seriously ill. The hospital was then earmarked to remain as the regional smallpox hospital, should it be needed again.

Regional and National Isolation Hospital

The hospital at Catherine-de-Barnes became the Regional Isolation Hospital in September 1966 and was kept on permanent standby, ready to accept patients at one hour’s notice. Over the years, the Department of Health reduced the number of beds at the hospital from 42 to 10.

Mrs Janet Parker, who worked as a medical photographer in the Department of Anatomy at Birmingham University, began to feel unwell on 11th August 1978 and was initially diagnosed with flu and then chickenpox, so was treated at home, and then at her parents’ home. She was admitted to East Birmingham (now Heartlands) Hospital at 3pm on 24th August and smallpox was suspected.

A diagnosis of Variola major, the most serious form of smallpox, saw her admitted to Catherine-de-Barnes Isolation Hospital at 10pm the same evening. The hospital’s Ward 1, in which she died on 11th September 1978, was still sealed off five years after her death, with all the furniture and equipment inside left untouched.

Mrs Parker’s parents, Fred and Hilda Witcomb, also caught smallpox whilst caring for their daughter. Mrs Witcomb, who had been vaccinated on the day of her daughter’s diagnosis, fell ill on 7th September but recovered and was discharged on 22nd September.

Mr Witcomb, who suffered from angina and diabetes, was also treated at Catherine-de-Barnes and died there on 5th September 1978. No postmortem was carried out because of the risk of infection, but an inquest at Solihull on 15th September 1980 was told that his cause of death was smallpox and a heart attack.

In 1981 it was announced that six other isolation hospitals across the country would be closed, leaving Catherine-de-Barnes as the only smallpox isolation hospital in Britain. The 24-bed hospital was chosen for its central location, and it was given a £150,000 revamp.

In 1985, the Coventry Evening Telegraph published an article featuring the hospital, which it described as the Marie Celeste of the NHS. Costing £40,000 per year to maintain, the hospital was the only one in the country kept on constant red alert in case smallpox should return.

Its caretakers of 19 years, Les and Doris Harris, had kept the building ready to accept patients at as little as one hour’s notice but the Department of Health had decided on a complete shutdown of the hospital, probably by the end of 1985, as smallpox was considered to have been eradicated.

The Coventry Evening Telegraph 12th April 1985 reported that Solihull Heath Authority, which managed the building, had asked Government experts at Porton Down microbiology research centre for advice on how to safely dispose of the building.

It was feared that the hospital, standing in four acres of picturesque grounds, would have to be burned to the ground in case the smallpox virus still lingered. This was the fate of Witton Isolation Hospital in May 1967. However, in July 1985, it was reported that all of the buildings at Catherine-de-Barnes were being soaked in a “mist of toxic disinfectant” (Birmingham Weekly Mercury, 7th July 1985).

Conversion

Following the fumigation treatment, the hospital site was given a clean bill of health. Solihull Council’s Planning Committee gave permission at its meeting on Monday 2nd June 1986 for the conversion of the former hospital, situated on green belt land, into 17 luxury private homes.

The conversion scheme was said to involve a lodge, nurses’ home, four ward blocks, a mortuary and a number of outbuildings. It was noted that the health authority was expected to put the site on the market.

The Birmingham Mail, 2nd September 1986, reported that the Catherine-de-Barnes site had been put out to tender until the end of September, with possible uses suggested as a public house or a company training centre.

The Birmingham Mail of 4th March 1987 reported that Black Country-based firm Three Oaks Finance Ltd had submitted a detailed planning application to convert the hospital into 17 flats and to retain the hospital’s Lodge House as a private dwelling.

If you have any further information about Solihull’s isolation hospitals, please let us know.

Tracey

Library Specialist: Heritage & Local Studies

email: heritage@solihull.gov.uk

© Solihull Council, 2024.

You are welcome to link to this article, but if you wish to reproduce more than a short extract, please email: heritage@solihull.gov.uk

Further Reading

Did a good turn for medical colleagues cost Janet Parker her life? by Andy Richards, Birmingham Live, 2018.

The Lonely Death of Janet Parker – Birmingham Live

Report of the investigation into the cause of the 1978 Birmingham Smallpox Occurrence by Professor R. A. Shooter

Solihull & Yardley Joint Isolation Hospital Committee Minutes 1895-1911 and Solihull & Meriden Joint Smallpox Hospital Minutes 1902-11 are held at The Core Library, Solihull. Please contact us to make an appointment if you wish to see these.

Leave a comment